On paper, the behind the scenes story being pushed about this joint North Korean-U.S. production is extraordinary: THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN is a film that took six years to make and was a historical first-ever collaboration between North Korea and a U.S. film company. The film was actually shot in North Korea with a North Korean cast and crew and was written and produced by Joon Bai, who was born in North Korea but immigrated to the United States in 1959, and starting in the late 1990s has made dozens of humanitarian trips to North Korea. He decided to make this film to spread his message of the suffering people of North Korea and their hopes for reunification.

So while there’s no denying that his heart is the right place, I’m not sure how much of this film is really of Bai’s vision. That’s because there is little in this film that isn’t melodramatic propaganda straight from the North Korean government via director Hak Jang. It doesn’t even attempt to be subtle with seemingly dozens of scenes of crying, dying, and suffering women and children to pull at the heartstrings.

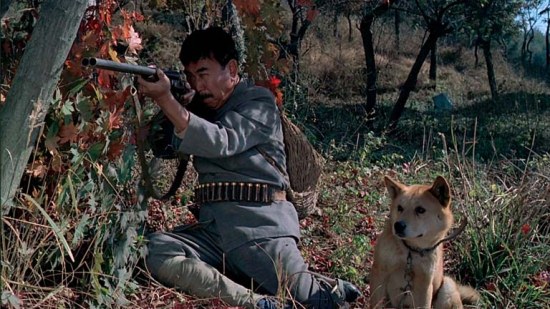

An opening title card tells the audience that this film is based on “true events,” which then fades into the movie’s framing sequence set in 1980 about a young man of Korean descent trying to figure out the details of his recently-deceased father’s life in North Korea. An old acquaintance of his father tells the story: Il Gyu (Ryung Min Kim) is a young man in Seoul, South Korea at the start of the Korean War, and on his way to school he is picked up by South Korean soldiers and forced into the army. During his first battle in North Korea, he sees the horror of battle and tears off his uniform. After being wounded, an old man and his daughter, Son Ah (Hyang Suk Kim) come across him and, thinking that he is a North Korean soldier, he is mistakenly rescued from the battlefield and nursed back to health. While in Son Ah’s care Il Gyu falls in love with her, but his nationality and Son Ah’s dedication to being a nurse are only the first obstacles that will come between them.

From a technical standpoint the film is archaic. While I understand the limitations of the production, the visual quality is so poor that it looks like a 1980s television movie. You would have a hard time convincing anyone this film was released in 2012. Scenes that take place in the 1970s are full of anachronisms like far more recent models of cars and computers, and there is even a sign for a medical conference that says “1992.” There are also structural problems, including two ill-fitting musical interlude 35 minutes into the film. 12 minutes later, there is a brief respite from the falling-in-love frolicking of our two leads to flashback to Gyu’s father giving a stirring speech against Japanese imperialism. The film’s dialogue (or at least the English subtitles) often sounds like it is taken straight from propaganda posters: “Let’s not live as shields for American bullets.” “Why do people whose faces are different from ours bring so much tragedy upon us?” “We must be strong so our children do not fear the sound of the enemy’s bombings. Our nation with its 30 million people must stand and fight for the reunification of our divided land. So all of us, together, can rise as one glorious nation.” I know Bai is a novice writer, but I certainly don’t think those lines came from him. But perhaps his fingerprints are still on the love story, which is pure melodrama. Son Ah is beautiful, virtuous, courageous, and selfless to the point of self-ruination. Il Gyu throws his best lines at her (like “I’m jealous of this mountain wind… it steals away your scent.”) but he just can’t crack her noble exterior. Finally, though the score is credited to a North Korean musician, it is so reminiscent of Ennio Morricone’s theme from Cinema Paradiso that they are lucky that sanctions will probably prevent him from prosecuting.

Though The Other Side of the Wind is making the festival circuit in America (and even won a few awards), you’d be hard pressed to find many Americans who would be sympathetic to the portrayal of the United States. Without exaggeration, every fifteen minutes during the Korean War scenes, the U.S. military are causing some terrible atrocity to move the narrative forward – bombing villages, destroying sacred temples, or setting masses of innocent women on fire (the last with absolutely no explanation). Even after the war, when one character is diagnosed with a deadly disease I expected the Americans to get blamed for that, too. When people say that mainstream American films like Zero Dark Thirty or Captain Phillips are propaganda, they’ve really never seen anything like this, especially since the film ends with a three minute sequence of the cast and crew singing a song advocating for Korean reunification.

Yet with all that in mind, I can’t help but recommend The Other Side of the Wind to those that will either be entertained by its sometimes-absurd aspects or will marvel that a film like this even got made in the first place considering the circumstances in North Korea. Despite only being released last year, it is in a lot of ways an instant historical curiosity. If you’re a student of international film you will undoubtedly appreciate the sentiment even if you can’t appreciate the cloying narrative or the outdated production values. As I said above, Bai’s heart was obviously in the right place, even if it seems the North Korean government did its best to remove his heart from this film.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN (Korea USA 2012, 102″)

Directed by In Hak Jang, screenwriter and producer Joon Bai

Now playing as part of the 2013 Korean American Film Festival New York (KAFFNY), October 24-26, 2013, at Village East Cinema

KAFFNY venue: Village East Cinema (189 2nd Avenue, New York, NY 10003)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.